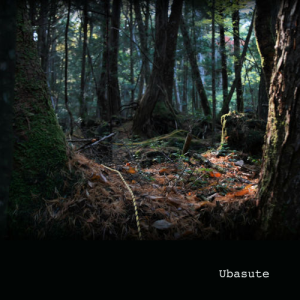

Title: Ubasute

Music to accompany an audio book.

Tracklist

Etude 10 (In the Bed of Lake Michigan)

Etude 23 (Secret Waltz)

Nocturne 31 (Sea of Trees)

Etude 33 (Comb)

Bagatelle 30 (El)

Sketch 33 (Father Composing)

Nocturne 2 (Cave of Ice)

Sketch 28 (Song Written In Empty Apartment)

Nocturne 20 (Food Underground)

Bagatelle 14 (Apology)

Etude 3 (Aokigahara: In The Shadow of Mt. Fugi)

Nocturne 4 (The Arthritic Hands of Izanami)

Etude 5 (A Short Conversation)

Nocturne 19 (Yomi)

Berceuse 5 (The Old Turntable)

Nocturne 34 (Cave of Wind)

Sketch 15 (Personal Files)

Bagatelle 27 (The Strength to Snap a Twig)

Etude 26 (The Antique Piano)

Excerpts from audio book “Tower of Waves”:

NARRATOR: In 1973, my father bought a three-room one bedroom, fourth floor apartment in north Chicago for twelve thousand dollars. Nothing about the purchase itself is interesting, really. He was forty-six years old and probably interested in drawing a little extra monthly income from rent, and even though my family lived near Kalamazoo, it wasn’t unusual for Kalamazooians to make investments in and business trips to Chicago from time to time.

What is unusual is that he kept this purchase, and any financials from it, secret until after his death, nearly forty years later.

***

NARRATOR: The bottom of Lake Michigan probably, most likely, nearly assuredly, has more once useful stuff than could possibly be imagined – and not just things that were once useful in Lake Michigan. Beyond boats and fishing nets, poles, lures, what-have-yous and never-could-catches, there is almost certainly an entire history of things that Chicago no longer wanted or simply lost grasp of: shoes and suits, bicycles, cars, vast storerooms of furniture, city blocks of storerooms, entire neighborhoods of asphalt chunks and old hydrant caps, cut-down saplings, arbolist equipment, light posts and street signs, not to mention crime evidence, weapons, bodies, and God-only-needs-to-sees. Tangles and tangles of the past, all sunk and sleeping in the rocky muddy bed. Sometimes I wouldn’t mind taking a U-haul of my baggage and just backing it in there myself. They should have paid helicopter flights for this reason, flights where you get about two miles out and then hover offshore and just throw your bullshit out the windows.

***

NARRATOR: The water bed took up the majority of the bedroom and the grand piano took up the majority of the living room, and other than an end table, a couple of lamps and enough of a kitchen to microwave an occasional meal, there wasn’t much to his father’s secret apartment. In fact, it was hard to understand why it was a secret at all.

“It’s a little tacky that he had a waterbed. Maybe it was always here or something.”

Rena paused on the other line. “Do you think that he, well, you know?”

“I thought that he might have, well, you know. In fact, I was pretty sure he had, well, you know. But looking at it, it looks like he came up here, ate frozen pizzas, wrote tons of short little piano songs, drank too much, and then slept crappily. It’s impossible to not wake up every other hour in that bed. No wonder he always complained about his back,” I walked back to the tiny bedroom and looked in. “It’s a little tacky that he had a waterbed. But if he was trying to impress anyone this wasn’t the way to do it. Maybe it was always here or something.”

“You almost sound disappointed.”

“I guess I had hoped …. I had hoped Dad was having fun or something. It’s kind of a male thing to think. I mean, Jesus a waterbed? I understand it’s some kind of eighties thing, but can you imagine fucking on one? I don’t know how you would get any leverage. Like trying to push a car out of mud while standing on a skateboard.”

***

NARRATOR: Myra shifts uncomfortably from foot to foot and I’m afraid she’ll fall over. She’s top-heavy like a cartoon bulldog. Our conversation has gone on longer than she intended and I think she’s trying to come up with the perfect nice innocuous thing to say to wrap it up.

Sometimes, she says, my father’s melodies still get stuck in her head. “I suppose that’s what happens whenever a song gets cut off unexpectedly.”

***

NARRATOR: The shower with a matted clump of hair in the drain. Tops of buildings lost in fog. My morning comes in half-awake snippets. On the El, pressed in with commuters, sometimes I imagine that we could all fall asleep at once and then wake with a jolt only to find that we’d tangled ourselves together in a big rat-king-like ball.

Some things completely go together for a short time and then just come apart naturally without any sense that they once fit at all. Take an icicle, for example. There’s one that hangs from a clogged gutter, up near one of my dad’s old windows – a dirty little dagger, an object completely defined by the temperature. When the sun hits it for long enough, each drop of water melts off and runs away in its own direction, depending. I don’t know that that means much. It’s something I still think about from time to time.

***

NARRATOR: There is a Chicago legend from the 1930s of the lost ice boy. Apparently they used to have a public ice skating built on the water around navy pier, until one year some greedy racketeering boys let a group of schools out on the ice in November, before it was really ready. The ice cracked and the kids made a mad scamper for the boardwalk. One of them didn’t make it back up. The local fire department spent three days cracking holes in the tops of the ice trying to fish around for his body. They never found it.

For years after that, they say that if you are out on the edge of Lake Michigan in the dead of the coldest winter, when the waves of water have frozen in mid-crest, and Lincoln Park is quiet and still as a cursed forest, you can hear an soft but persistent pounding noise coming from deep below the surface of the ice. It’s been explained as pockets of air and rock being pushed around by the undertow, but many people still say it’s that boy under the water, hoping to let you know where he is so you can let him out.

***

NARRATOR: The estate sale was for a former Park Ranger in the Aokigahara National Park. Everyday he’d wander the Japanese suicide forest, hoping to find people that had wandered away from their families and had set up camp in the stumbling tangled mess of roots and dark leaves.

If you look up the Aokigahara on Google, you’ll find pages of images of dead people. But that isn’t what the Park Ranger usually found. Mostly he’d find the left-overs. Bodies and suicide notes: these were the easy things to return to relatives. But often small things lay scattered about – once useful things – that had been taken with the person to the forest. Objects to pass the time until they died.

The Park Ranger collected these things from the unidentifiable and unclaimed and set up a little museum in his house. It grew and grew over the years. He moved it with him and his family to Chicago. Now his family was selling it off.

One bad idea could split in to endless variation. His collection was lined up on plastic folding tables, rows and rows of little sad thoughts from another country, each individually priced, each with a little card with the date that it was found, and each with a description of where it was. There were iPods and magazines and books and books and books. Lots of toys, dolls and trinkets. Strange collections: A bowl full of little saws. A jar of barber combs. Little remembrance bracelets. A baby booty. And many musical instruments.

***

NARRATOR: My father was an angry man, it seemed, a lot of the time. Like a malfunctioning radio, it would pop out of him in little bursts of static. Frustration, I suppose, was more what it was. I would have had no idea that he spent any time playing an instrument, let alone trying to write any music.

I wonder what it is about the arts that cause people shame. Why would my father wander off to Chicago and hide in anonymity just to play piano? Was he afraid that he wouldn’t let him play piano around him? If he didn’t want us to hear him on piano, why try to write out the music? Why record himself on a tape recorder?

On the hundreds of random music staffs, each page shows his anger. These notes sound more like my dad than the recording itself. Quickly scribbled and crossed out. “Why would anyone listen to this bullshit? It sounds like loose pieces of dead skin.” and “The Berceuse is like listening to someone slowly die from Alzheimer’s.”

But the sounds on the tape recorder are different: halting, unsure, kind of hollow. It’s like listening to someone learn to speak with stutters and hesitation. The upstairs neighbor is wrong – there is nothing about this music that I find relaxing. His piano playing come and went in short twisted paths, in series of uncomplicated melodies, ticking out tedious simple rhythms. All I hear from the tape are lost moments. At the very best, I can say that if one of the songs disagreed with me, I could count on the fact that it would end quickly.

***

NARRATOR: According to at least one source, the demographics for people most likely to survive a hurricane includes people that own waterbeds. It’s a wild list of random connections without real cause or correlation behind it. Beyond people that own waterbeds (88% likely), there are dog owners (82%), people with two or more can openers (73.2%), women or fish (68.2%), and men that rigidly obey flag protocol (63%), among others.

Years ago, I had a girlfriend that found this list in a New Orleans tabloid and cut it out to give to me. She said, “Translation: Whatever you decide to do probably doesn’t matter very much.” Then she broke up with me two months later. Man, I could probably write ten years worth of songs about that girl. I won’t. I have things I have to get back to.

Download Album

Download Sheet Music